This blog is also available as a video and you can see it here:

I was talking to a friend a few weeks ago and they were feeling a bit frustrated about a new programme at their work (a really well known UK national company).

I listened carefully while they explained how HR were trying to encourage everyone to be more agile. Well, I love a bit of agility and didn’t think that a sensible person like my friend should be frustrated by it, so I asked them to tell me more.

Probably no one is surprised that agile practises are bursting out of the IT world that adopted the thinking as its own. Agility is the up and coming business bingo buzzword!

But what was it exactly that was bugging my friend so much? They explained that home working and flexible hours were the two main tactics being deployed to increase the enterprise agility.

I looked a bit troubled and they sensed I would be an ally! Full marks for perception!

Agility is in my DNA, I first started to consciously codify it in 1990 when I was given a book called The Goal by Goldratt and Cox. If you haven’t read it, I urge you to do so.

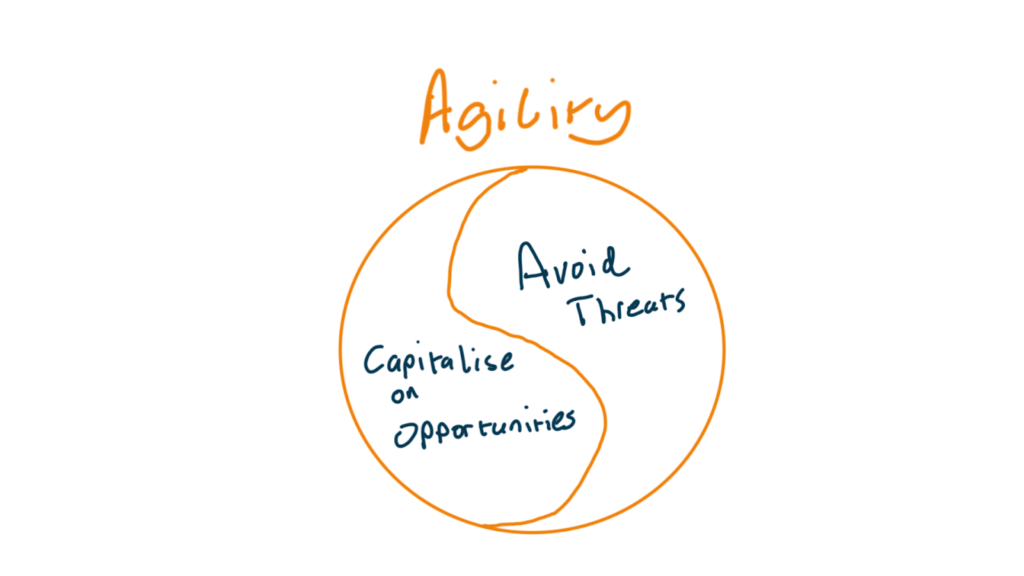

So what is agility? Agility is the ability to change direction really quickly when we need to.

And why might we need to change direction quickly? Because predicting the future is hard and unexpected things happen that we can’t always reasonably be prepared for.

There are two big areas where high levels of agility will help us create more long term value

- High agility increases our ability to evade threats (or compensate for our weaknesses)

- High agility increases our ability to capitalise on opportunity

In business, and life, those are good things!

In the remainder of this blog, I’ll elaborate more on the unpredictability of our world, the nature of transformation programmes and the things we can do to increase our personal and business agility.

The first and most important step is to start thinking about agility, what it is, what it isn’t and why it might be good if we had more of it. When we have those things more clearly ordered in our minds, the path to increased agility becomes so much clearer.

What does it mean to be agile?

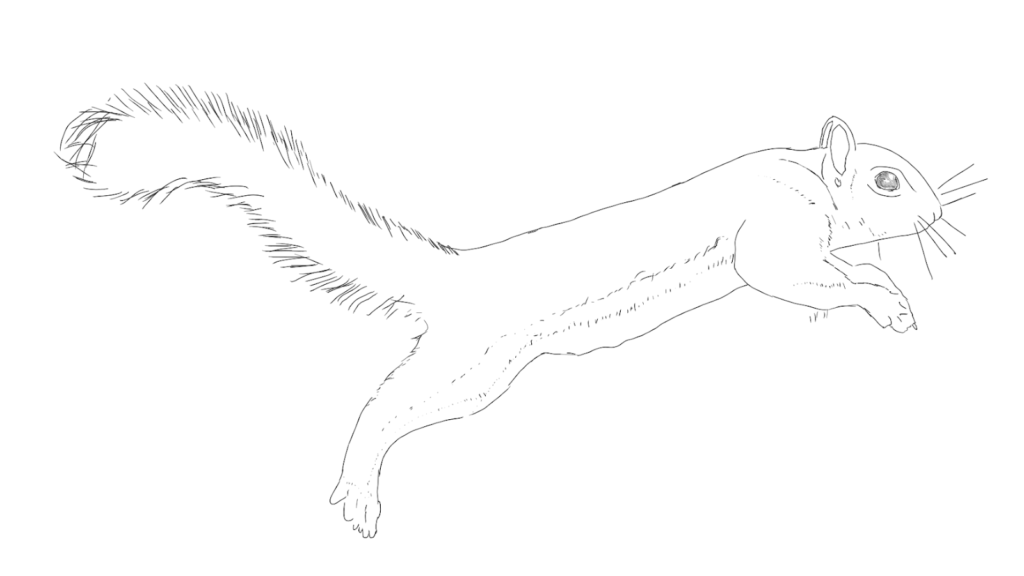

I was planning this blog in my garden office one day and I was watching two squirrels. Their agility is beyond astonishing and they raced across the garden, up trees, down trees and jumping from tree to tree. They are masters of their domain and display dizzying states of agility as easily as breathing.

They keep a sense of their context (the flimsiness of the branch they are currently racing along, each other, the location of food and the presence of predators) and have deep instinct on when it’s best to change direction.

Over millions of years, evolution has rewarded agility and we can draw many lessons from it (If you’d like to see how evolutionary thinking can be used to solve hard problems, you might enjoy my blog: Darwin and the Travelling Salesperson) .

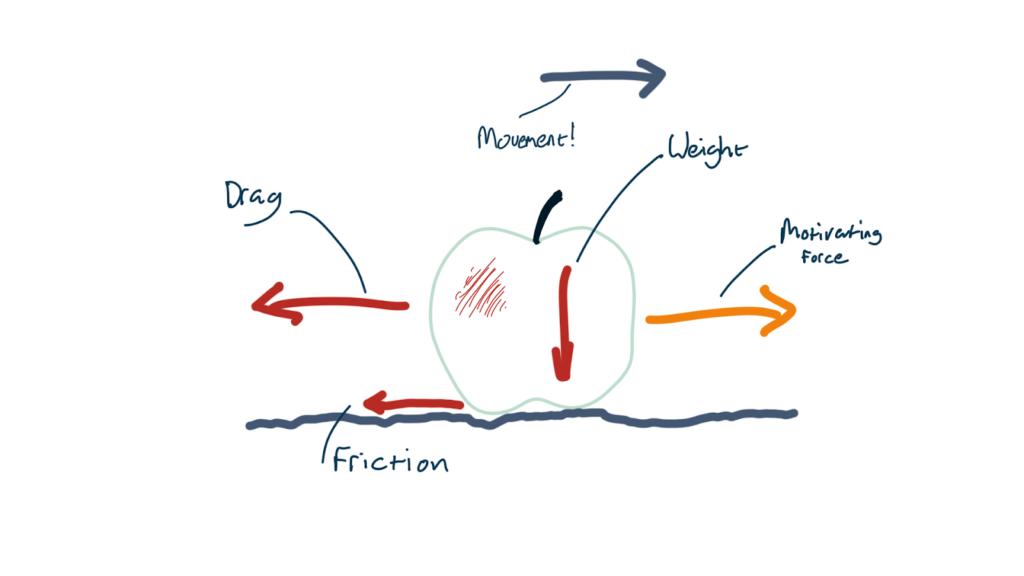

If we also turn to physics for inspiration, what might we learn there?

- We need a force to make things move in a new direction (change velocity)

- Heavy things take more force to achieve the same velocity

- Friction keeps things where they are

- Drag tries to slow them down

- To sustain the movement, we need to continuously overcome these forces and energy is consumed when we do

When the motivating force is great enough to overcome the static friction created by the weight and the surface conditions then our apple will start to move. As it does so, drag is created that will try to slow the apple down, impeding the movement.

Strictly, I think that drag and friction are classes of the same thing but it’s helpful here for us to imagine friction as the thing that stops us getting started and drag like wading through treacle.

“Ok,” I seem to hear you say, “Squirrels, forces, friction, drag and weight are all very interesting (well, sort of!) but what do they have to do with increasing the agility in our businesses?“

They help us build a model or a framework that we can use to guide us when considering activities that may (or may not) increase our agility.

Let’s go through them one by one:

Motivating Force

In business, our motivating force comes from a compelling business case told with passion, enthusiasm and credibility by a leadership team who are committed and can allocate the resources we’ll need for the journey. If we “do this”, we’ll “get that”.

Candidates for the business case appear when we look outwards to the market for opportunities or threats and build a model of what we would need to do, how much it would cost, how long it would take, what benefits we would reap and our certainty that we understand those things correctly. When we’re certain enough of the numbers and have convinced the key players that we should move then we’re good to go and we can start to apply our motivating force.

Strong motivating force from effective leadership that’s always aware of the context leads to higher agility.

On the other hand, ineffective leadership that ignores the changing context, changes its mind every few days, has unresolved conflicts, has poor judgement about things that matter and struggles to communicate has almost no chance of increasing agility. The teams will be in a spin, transformations will fail, the status quo will prevail and as the context changes, eventual demise is almost inevitable.

If you’re interested in using values based leadership to help boost your motivating force, you might like my blog: Are values in business our fair weather friend?

Weight

For some things, bigger is better. Economies of scale and all that.

For some, bigger is most definitely not better.

Team size is a great example where bigger means harder.

Keeping everyone informed, heard, aligned, effective and happy gets exponentially harder as the team size increases. So big teams are an example of weight that requires more motivating force when you need to change direction.

Work in progress is another example of the weight that transformation teams need to carry. If we have 10 teams of 7 people working on a 6 month phase, the sheer volume of work is huge. Any changes in the context that require a change in direction will have a dramatic effect. And if it was hard to predict at the beginning of that phase what the impact would be on the business when the phase was deployed (#spoilerAlert it is hard!), predicting the impact when the external context has changed can be almost impossible. We need to deploy and observe the impact. That creates our new context which probably looks somewhat different to how we thought it would. A new and unpredicted context requires a new plan.

If the plan itself is so heavy that the prospect of replanning daunts us, then our agility is reduced.

If our project is littered with dependencies between stages or phases, then the weights compound together and the motivating force has to work harder and harder to maintain the agility that we need.

There can be more examples of weight such as: number of sites, number of customers, number of products, brand capital, business maturity, business stability and regulation.

It’s good to try and identify them for each transformation we look at and then consider how we can reduce the weight, increase the force or reduce the distance we need to travel.

Friction

Friction is the thing that stops us making a start. In physics, we need to apply a higher force to a stationary object to get it moving and overcome the inertia that applies.

The same is true in business and life. Kick off events are run for a reason. They’re a great way of helping everyone to understand what’s happening, why some change is needed, what we hope to achieve, what the journey will look like and what we need everyone to do.

But if we don’t follow up our kick off event with the steady, continuous and compelling motivating force, then the initial movement will fade away and everything will grind to a halt. Leadership credibility is shot and our eventual chances of success have been harmed.

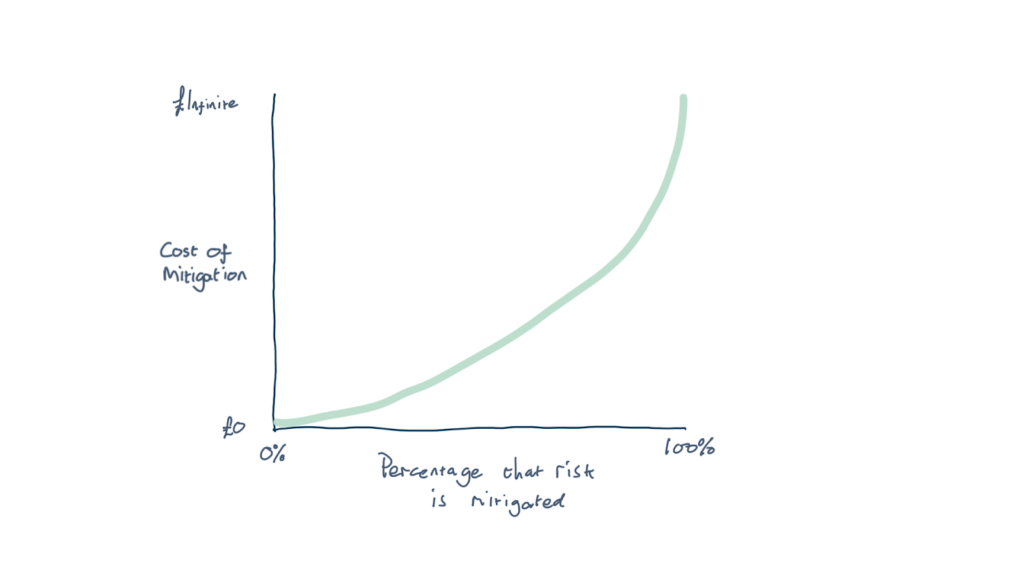

Where there is a strong (excessive?) aversion to risk, significant friction can be found in the project approval processes. Anything that seems to lack certainty is attacked unless completely mitigated and nothing can start unless the plan is foolproof. In some environments, this could be the proper way to behave. The friction that behaviour creates is huge and eventually innovative people will be driven underground, out of the business or silenced.

Educating the whole business to think rationally about risk is critical to reducing friction and increasing agility. Optimising the trade off between accepting the risk and mitigating against it can never be a precise science. We must take reasonable steps to identify the more probable risks and then taken appropriate actions to mitigate against them. If you think there is subjectivity in that statement, then you are correct. There are always more risks that can be found and there is always more we could have done to mitigate. It’s the job of leadership to make sure that appropriate risk management is in place and then support the teams in their work.

Friction can also appear when our businesses don’t have any spare capacity to search out, evaluate and initiate transformations. Many people shouting that something must be done, but no one that can actually fit anything else into their existing schedules. And no one in leadership who can create capacity by stopping some activities. Even without transformation considerations, the normal random variations of business life means that running at very high utilisation causes our organisations to bind up and stops us being all that we can be. We can reduce friction by firstly having some spare capacity on hand and then by getting good at creating more capacity quickly.

Drag

If friction tries to maintain the status quo, then Drag tries to slow the progress down.

If our people aren’t skilled in the tasks needed then we see drag.

If our teams can’t pull together, dividing the work, continually arranging themselves with minimal supervision to optimise their throughput then we see drag

If the interplay between the teams is fraught with misunderstanding, disagreement, treading on each others toes and letting things fall through the gaps then we see drag.

If the rest of the organisation seems to conspire in creating barriers and attempting to maintain the status quo then we see drag

If there are competing teams with the best intentions but attempting to pull the organisation in different directions then we see drag.

Drag is difficult to fix when we see it.

Drag is best tackled by preparing far in advance for the inevitable moment when transformation becomes critical for survival. Don’t wait passively for that time. Take action to prepare while the sun is shining. Just as experts in martial arts practise their kata in the dojo, so must we practise the skills that are required for transformation:

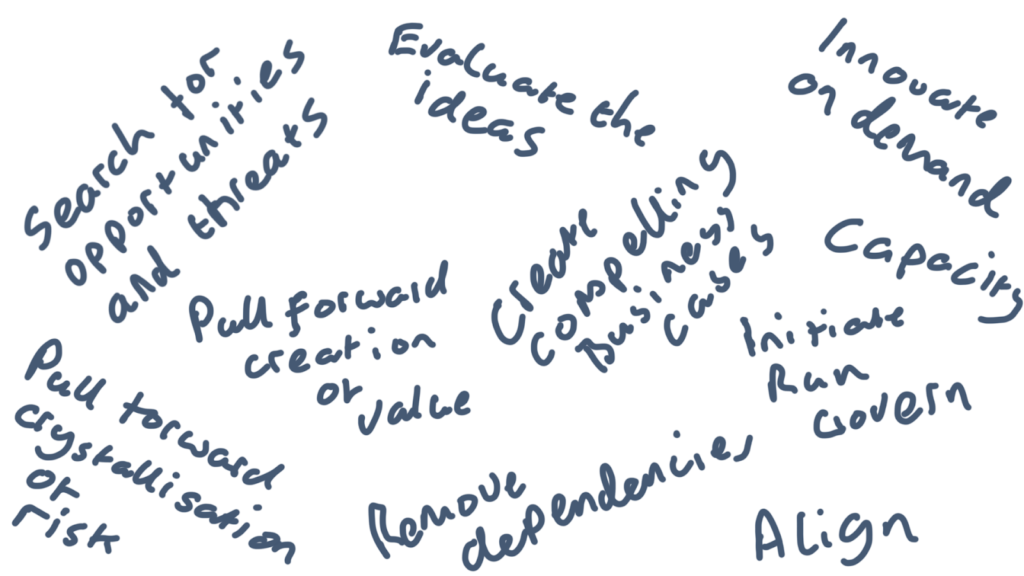

- Searching the context for opportunities and threats

- Innovating on demand to conceive multiple ways to capitalise / avoid them

- Evaluating those ways:

- Quantifying the benefits we could reap

- understanding the resources we’ll consume to get there

- Understanding the time frame for consuming resources and reaping benefits

- Understanding the risks and ways they can be mitigated

- Choosing a good path for mitigation

- Finding ways to accelerate the crystallisation of risk

- Finding ways to accelerate the creation of value

- Finding ways to remove dependencies in the plan to create value

- Compiling all that data into a compelling business case

- Telling it like a story in short, medium and long forms so that people want to listen and retell it to their colleagues

- Creating capacity to allow the transformation to run

- Initiating transformation projects and programmes

- Running transformation projects and programmes

- Governing transformation projects and programmes to ensure we are always on track to create the value

- Aligning our whole organisations behind transformation projects and programmes

- Learning lessons as we go

- Framing and learning from the failures (not initiating a witch hunt so we can punish those who could not deliver the business case they so compellingly sold!)

These are not trivial skills. To get good at them is hard and we must not underestimate their importance. If you are interested in getting better at innovating on demand, you might like my blog: Five tools for innovation mastery

And we must not become paralysed into inactivity because we are afraid that our skills are inadequate. They are always inadequate! We must be truthful with ourselves, keep our eyes open prepare for remedial work when bad things happen, which they will, and then seize the moment.

Fake certainty

Fake certainty is an antipattern for agility. When we’re sure that we know what’s going to happen, it makes us lazy. Fake certainty gives us the belief that we don’t need to keep checking the context. Why bother, we know what’s going to happen.

So our caveat to help us have more agility is: “Beware Fake Certainty!”.

By necessity, our business case will contain a description of our brave new world, the route we’ll take, the costs we’ll incur on the way and the bounty that awaits the victorious when we arrive.

There will be plans and financial models with forecasts aplenty. But the bigger the change and the longer the journey, so our trust that these numbers will be accurate must decline.

Sometimes, it’s comforting to cling to this frozen forecast of a promised tomorrow. We may be tempted to bolt it down and encapsulate it in resin so it survives the ravages of time and people can be held to account if the transformation fails to materialise as predicted.

But the forecast is fake certainty and embracing its fakery forces us to think and act differently.

When we accept that it’s fake, we must arrive at some logical conclusions:

- Perhaps our prediction of how customers will behave in our new world is incorrect.

If so, how can we always have the best understanding of their likely behaviour?- Show them our work as early and as frequently as we can

- Whilst showing is better than not showing, it’s still fake. Only when we deploy can we understand the effect we are having.

- Perhaps our prediction of the work and difficulties we’ll face on the journey is incorrect.

If so, how can we find the areas where our prediction contains the most risk and create more certainty?- Put aside the temptation to make progress by doing the easiest bits of the transformation early on. All it guarantees is that we burn money.

- Look for the hardest and riskiest parts of the project where failure would mean reduction of benefit. Do proofs of concept as early as possible so we can increase our certainty of predictions

- Look for the transformation components that are examples of well understood but lengthy re-engineering. Delay those as much as possible.

- Perhaps the benefits we’re banking on won’t actually be delivered through our actions.

If so, how can we get the best understanding possible?- Create something that looks sufficiently like our transformed business for us to actually test the impact it will have.

- Deploy it and make the conditions as lifelike as possible

- Then measure the impact, and make sure we’ve done what we can to remove our biases and extrapolate as best we can.

- Perhaps the passage of time will create changes in our context that will render all our forecasts more unreliable?

If so, how can we reduce the length of time the project requires before benefits are achieved?- Break down our programme into smaller components and work tirelessly to understand the exact causal chain that leads from activity to benefit. If the benefit can’t be stated in some mix of: selling more, cutting costs and increasing margin, then question if the thing we’re looking at is actually a benefit at all.

- Then do the best optimisation we can for the activities that lead to the biggest and most certain benefits with the least risky costs.

- Two things are pretty certain:

- Time changes the context so long programmes are more risky than short ones

- When we deploy something, we change the context and the certainty that our originally planned “next step” is still the best “next step” reduces.

In short:

- The rewards we hope to achieve are uncertain and should be commensurate with the costs we predict and the risk that those costs will be wrong.

So what could be our advice to help us increase our agility so we can capitalise on the opportunities and avoid threats? What will help us to become masters of the transformation domain like autumn squirrels effortlessly, dizzyingly dancing through the minefield of fake certainty?

I believe that some good answers to that question are contained in the words above!

And to sum it all up and give you my advice as succinctly as I can:

- think hard about what agility is

- think hard about why you might want it

- think hard about how you can achieve it

But what about my friend and the attempts at their workplace to increase agility through homeworking and flexitime? I suspect that my friend’s business may get some benefits from those tactics but I don’t believe they will actually go very far to increase agility. In fact, if I had to call it, I’d say that all other things being equal, they’ll probably reduce agility!

If you’d like to discuss any of these ideas with me, please give me a call!

And finally, I hope my ramblings have gone some way to help you to see more clearly the prize and I wish you all the best with your own hunt for personal and business agility

Good luck